Prevalence and severity of MS across the world – can new research explain the patterns?

Studies provide insight into the links between MS prevalence, severity, latitude and healthcare spending

Last updated: 23rd September 2022

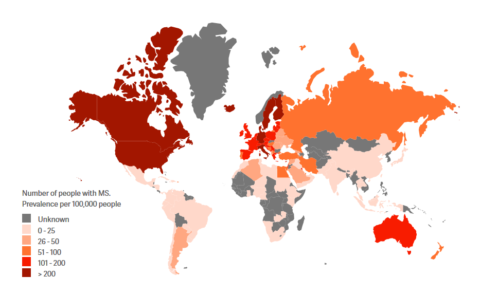

An association between the number of cases of MS (its prevalence) and where people live in the world has been known for many years. As shown by the Atlas of MS, we tend to see a greater prevalence of MS in countries or areas that are at higher latitudes i.e. further away from the equator. This is thought to be related to decreased sunlight/UV exposure, partly linked to lower levels of vitamin D.

Less is known about the relationship between latitude and the severity of disease experienced by people with MS. A study published in April 2022, using data from the international MSBase Registry, looked in more detail at the link between latitude of residence, UVB exposure, and the severity of MS as assessed by the EDSS scoring system. Results showed that there was a relationship: more severe MS was associated with living in higher latitudes, but only in temperate parts of the world (latitudes greater than 40o, which includes the majority of Europe, Canada and the northern half of the US, and the southern parts of Argentina, Chile and New Zealand). For example, people with MS living in Copenhagen, Denmark, are more likely to have severe MS than people living with MS in Madrid, Spain.

In addition, disability progression was faster in people with MS who had lower levels of sunlight/UVB exposure in their early years of life, as well as in total across their life course. However, the amount of UVB exposure did not fully explain the relationship between latitude and MS severity, suggesting that other factors are also important. The authors propose that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) could be a factor, as the prevalence of EBV is greater in higher latitudes.

Healthcare spending and MS prevalence

Another important study, funded by the National MS Society in the US, and led by researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in the US and University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia, has also uncovered new findings relating to latitude and MS. To study this, the researchers analysed the prevalence of MS in 203 countries and territories. They then correlated this with a range of factors including GDP, health expenditure, income levels, availability of MRI machines, numbers of neurologists and lifestyle factors such as obesity and tobacco use. In this case, the researchers were looking at MS prevalence only, but found that in addition to latitude, there was a correlation with countries’ spending on healthcare.

Why is this finding important? In order to diagnose MS, it requires a trained neurologist who knows what to look for, and access to diagnostic testing, such as MRI machines. Countries that cannot afford these trained healthcare professionals and equipment are less likely to be able to diagnose MS.

As Dr Deanna Saylor, the study author, describes:

‘This leads to under-diagnosis of MS and under-reporting of MS prevalence, which then leads to the belief MS “doesn’t exist” or is “extremely rare” in these regions. This results in healthcare workers receiving little training about MS, so they are unlikely to even consider it as a possible diagnosis, thus further ensuring the cycle of under-recognition and perpetuation of beliefs that it is not an important disease in that country/region. Our neurology team in Zambia regularly diagnoses MS, showing that MS is present if neurologists are present. The absence of data does not equate to the absence of disease.’

These studies underline the urgent need to improve access to healthcare – in particular, to neurologists with expertise in MS and relevant diagnostic equipment – so that people across the world can have a timely and accurate diagnosis of their condition. This is why MSIF supports the adoption of the WHO’s global action plan for epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Early diagnosis can lead to early treatment with DMTs, which can limit the accumulation of disability across the life course. Understanding the likely course of their disease in terms of severity can help healthcare professionals select the best treatments and care for people with MS according to their individual circumstances.